From Search to Ask: How AI Is Changing Our Relationship to Information & Learning

From the Search Generation to the Ask Generation — our relationship with information has fundamentally changed.

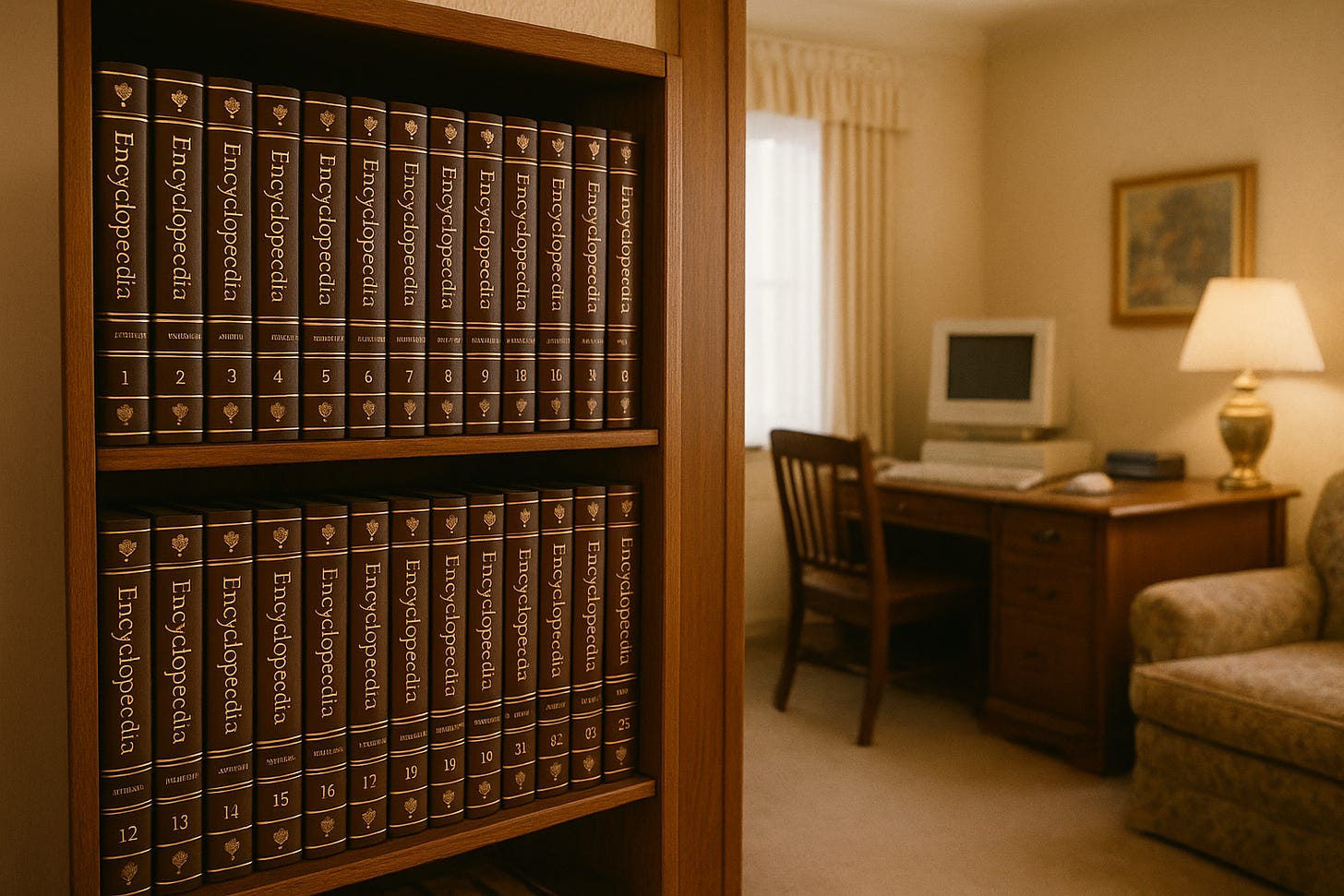

I still remember the day the Encyclopedia Britannica arrived at our house.

Not in a cardboard box from Amazon, but hand-delivered by a salesman my father invited into our home (something my father rarely did). The leather-bound volumes and golden edged pages gleamed as they were proudly displayed in our living room — on their own shelf — like a shrine to knowledge.

My parents, both immigrants, had worked hard to give us what they never had. And for them, this collection of books was a symbol of arrival. Of opportunity. Of education.

I remember flipping through those volumes as a kid, carefully turning pages, looking up entries for school assignments on volcanoes, photosynthesis, and Thomas Jefferson. And I especially remember my teachers warning us: Don’t just copy what it says in the encyclopedia! You were expected to read it, understand it, and then put it in your own words. There was no Ctrl+C/Ctrl+V. No hyperlinks. No instant summaries.

The struggle — finding the right book, the right page, the right phrasing — was part of the process. We were being taught the basic skills of research, of building our internal knowledgebase.

Then Came Search

When the internet arrived in full force, it blew the doors off that whole model. We didn’t need a curated set of books (or Encarta CDs for those willing to date themselves). We had everything, everywhere, all at once. Search engines like Google gave us access to more knowledge than any single book, or library full of them, could ever contain — and made it accessible in milliseconds.

And so, the search generation was born.

You typed in a few keywords. You scanned the results. You clicked, and accessed information. It was a revelation — and a revolution.

Suddenly, the rules of research were different. We weren’t just looking at a single entry in a coveted source of truth. We were given a curated list of sources — and there were a lot of sources. But they were ordered.

We had to learn to judge the credibility of each one. To learn the difference between a promoted source from an organic source. We had to learn to commit a successful search — often reverse-engineering our questions into keywords.

Google didn't give you the answer. It gave you places to look for the answers.

The rise of the Ask Generation

But searching for answers is changing — fast.

With AI tools like ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity, and Gemini, we’re entering a new era. One where we don’t search, so much as ask. We’re not given a list of sources to review and assess. Instead we’re provided a single synthesized answer. And if we don’t like the answer, we just ask again. Or rephrase. Or go deeper.

My kids, for example, don’t “Google it” anymore. They “ask ChatGPT”. And instead of digging through sites or parsing through PDFs, they expect the answer to come in clear, conversational English — formatted, summarized, and ready to go.

But, unlike a Google search, it doesn’t typically end there. Because we can discuss it, have a conversation about it, dig for more information, or ask for another perspective.

It’s a different relationship to information.

It’s not about finding. It’s about dialogue.

It’s not just a search engine. It’s a conversation partner.

And that’s powerful. Because while books gave us information, and search gave us speed, asking gives us engagement. The ability to explore a topic the way our minds actually work — through curiosity, follow-up questions, nuance.

While books gave us information,

and search gave us speed…

asking gives us engagement.

But What About the Struggle?

Of course, this shift comes with it's own concerns. One of the most common (and valid) is that we’re losing the struggle — and therefore, the learning.

There’s an old idea in education that the learning happens in the friction — in the messy process of making sense of things. If AI just gives you the answer, what happens to the process of grappling with complexity? What happens to our ability to analyze, synthesize, or think?

It’s a fair question. And one that is validated in data. In a four-month study [PDF] by MIT, found that people who relied on AI from the start of a writing task had lower memory recall, less neural engagement, and felt less ownership of their work.

I’ll admit, even as a fervent advocate of AI, I wrestle with this myself — especially as a parent.

But I also think the fear that using AI completely bypasses the learning process, misses something deeper: It’s not the asking that’s the problem — it’s how we ask it, and what we do with the answer.

When used lazily, sure, AI becomes a crutch. But when used intentionally, as part of the process, it becomes a coach. It invites you to keep going — to test assumptions, to dig into context, to explore “what ifs.” The best use of AI isn’t for regurgitation. It’s for advancing our own reasoning and building deeper understanding.

I recently spoke to an engineer friend who uses AI to help solve complex problems he is working on. In one particular instance, he told me, the AI didn’t give him the answer — instead, it was the process of building the ideal prompt that led him to realize how to solve the problem on his own.

And in that sense, maybe AI isn’t replacing the struggle. Maybe it’s just relocating it. From “Where do I find this information?” to “What do I need to know?”. From “What’s the answer to this question?” to “How can I use this answer to help me do this thing better?”

The struggle — I argue — is shifting from search mechanics, to critical thinking.

That same MIT research backs this idea. When participants engaged first on their own — thinking, drafting, struggling — and then brought in AI, their learning improved. They were better able to compare, refine, and reflect. In other words: AI doesn’t necessarily mean we’re eliminating thinking. But how and where that thinking happens, matters.

We Need to Teach a New Kind of Literacy

Admittedly, this isn’t as simple at it sounds. This shift requires a new kind of literacy. A new kind of understanding of how we can work with AI. Not just how to use the tools, but how to interrogate them. To ask better questions. To spot hallucinations. To know when a synthesized answer is insufficient.

Just like we were taught not to copy directly from the encyclopedia, we need to teach today’s learners (and employees too!) not to copy-and-paste from AI. Not because it’s cheating — but because it short-circuits the chance to understand.

That also means rethinking how and when we introduce AI into the learning process.

Start with independent thinking — let people draft or explore ideas without AI. Building a thoughtful premise, forming an idea, and then creating a powerful prompt that delivers the expected outcomes (or solves their problems in the process!).

Then, bring AI in to compare, refine, or challenge those assumptions and ideas. Design tools and prompts that encourage revision and reflection — not just instant answers. And just like we taught kids the Dewey Decimal System pre internet, and web literacy in the search era — we need to teach AI literacy now: how to prompt thoughtfully, evaluate critically, and decide when to trust… and when to think twice.

Knowing how to ask is just the beginning.

Knowing how to challenge the answer — that’s the skill we need now.

We’re at an inflection point in how we interact with knowledge. AI won’t make us smarter by default. But it can help us become more thoughtful — if we treat it not as an answer machine, but as a partner in thinking.

And those are the skills we need to be teaching. Because those are the skills we’ll need in a workforce in the future. Not just people who don’t trust AI — but people who can decipher and use AI to get the answers we need to drive progress.