Preparing Students for a World Shaped by AI: What Educators (and Parents) Need to Know

Educators are front lines of the greatest shift in learning since the internet — coupled with demand for an AI ready workforce. How is AI redefining learning, and what do students need to compete?

I’ve spent years working on AI strategies with executives, technologists, and cross-functional teams across enterprises, nonprofits, municipalities, and startups. Increasingly, though, those conversations have expanded into education — with teachers, administrators, and curriculum leaders, at K-12 and even higher-ed.

At every level, educators are working hard trying to make sense of the real impact of AI — and what it means for the future of teaching and learning.

And that matters a lot, especially to the businesses and organizations building their AI-ready strategies. Because education isn’t separate from the future of work — it’s the front door to it.

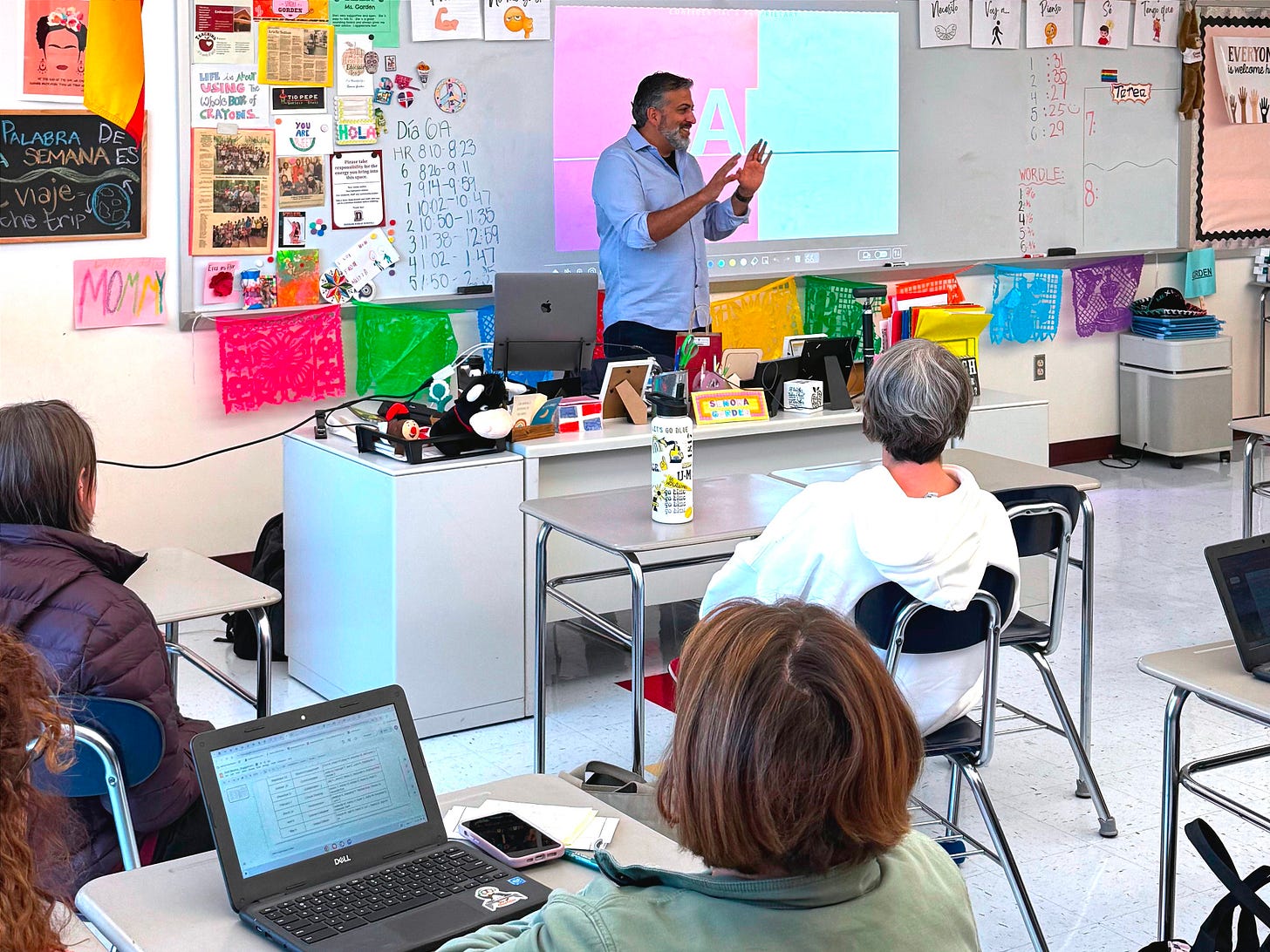

I recently ran three professional development sessions on Demystifying AI for teachers and administrators. The pattern of feedback was remarkably consistent: there is an uneasy excitement about AI.

Everyone can feel that this is a moment, not just another tool. And yet, just under the surface, there’s anxiety — about cheating, the loss of creativity, student mental health, and, yes, whether teachers themselves will someday be replaced.

We already know AI is reshaping the workforce.

What’s less visible — but no less real — is how it’s reshaping education.

Not whether it will.

But how it already is.

And that friction point is painfully obvious once you see it. An analysis by the Public Policy forum Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) way back in 2023 stated that “rapid advances in generative artificial intelligence will likely disrupt many aspects of digital education.”

AI capabilities are advancing on a 3–6 week cycle.

Education systems operate on a 3–6 year cycle.

This mismatch isn’t the fault of educators. It’s structural. Education systems are designed for stability, consistency, and consensus — all good things when the ground is steady. Less ideal when the ground is shifting every quarter.

So if the goal of education is to prepare students to enter — and shape — the world they’re stepping into, then adapting to AI isn’t optional. It’s foundational.

That’s my premise: not that AI demands we reinvent education from scratch, but that we intentionally connect what schools already value to the realities of the world AI is reshaping.

Because the skills educators have always championed — critical thinking, writing, questioning, analysis, synthesis, creativity, collaboration — are now the exact skills AI makes even more essential.

And one of the clearest signs of this shift is what I call the move from Search → Ask.

From Search to Ask: Why This Shift Matters More Than We Think

For twenty years, we built the web on top of search.

Typing keywords. Skimming links. Comparing sources. Piecing things together.

The friction was, at times, annoying. But it followed an instructional path. Although students could shortcut the work of finding the source of information — they still had to dig and sort through the chaff to find the grain of truth.

The struggle was learning to use search effectively as part of the learning.

But AI has collapsed that entire workflow into a single behavior:

Ask.

One prompt → one answer → minimal friction.

Today, students don’t have to look, navigate, filter, or evaluate before getting to the answer. And whether we love that or hate it, the shift is happening at a scale we cannot ignore.

But here’s what makes this so important for educators:

Search was always about finding.

Ask is about delegating.

When we use AI, we aren’t simply accessing information faster — we’re outsourcing cognitive effort. The work of sifting and sorting and making sense of the often disconnected and disparate pieces of information. Not maliciously. Not entirely out of laziness (although, yes, out of laziness). But because the tool makes that delegation incredibly easy.

And that changes the role of:

reading

writing

research

note-taking

synthesizing

and even how students build confidence around what they know

In that light, it’s easy to view AI as a threat. And as a parent, I empathize with the concern that the laziness will win out. I do worry that the ease of asking versus searching could erode the “aha moments” and the learning in the struggle.

As one teacher put it to me, “it feels a lot like we’re letting our kids play with fire.”

But fire isn’t necessarily destructive — if used in the right way, it can also be transformative.

The shift from Search → Ask doesn’t eliminate the need for critical thinking.

It increases it.

Because when students receive a clean, confident, well-phrased answer instantly, what we really need to know is — do they know how to question the answer?

Do they know how to check sources?

How to compare perspectives?

How to detect hallucinations?

How to notice when something “sounds right” but contains subtle inaccuracies?

How to push past the first answer, ask a better one — or better yet, challenge the AI’s thinking?

And to be clear, these are not new skills — they’re the same skills teachers have been pushing since before “Googling” became a verb — but the urgency is new.

AI doesn’t make these skills obsolete. It makes them non-negotiable. And educators who understand that, become irreplaceable: helping students build the intellectual muscles that let AI become a tool for learning, not a shortcut around it.

The Emotional Shift: AI as Companion, Not Just Tool

One of the most revealing — and honestly, most concerning — discussions in my PD sessions came from this simple question:

“How many of your students are using AI… not academically, but emotionally?”

Blank stares.

Then slow nods.

Then stories.

It tracks with what national data is already showing: Over 70% of teens report using generative AI as a companion, not a homework shortcut.

Not to plagiarize.

But to talk.

To vent.

To process feelings.

To ask questions and get advice on things they’re too embarrassed to ask adults, or too ashamed to engage their friends with.

This isn’t hypothetical.

It’s the water our kids are swimming in.

AI isn’t just reshaping how students gather information.

It’s reshaping how they relate to themselves, their peers, and the world around them.

We cannot address AI in the classroom purely as an academic integrity issue. It’s a mental-health, identity, and relationship issue as well. And educators will increasingly be on the front lines of it — whether they want to be or not.

What AI Is (and What It Isn’t)

Before educators can meaningfully guide students, they need a baseline understanding of what AI actually does.

I broke this down in the PD sessions in plain language:

AI is:

A pattern recognizer

A probability engine

A system trained on enormous datasets

Good at summarizing, simplifying, synthesizing

Good at generating first drafts, not final answers

Good at revealing patterns across sources

Stochastic — meaning the same question rarely returns the same phrasing twice

AI is not:

A truth machine

A moral compass

A teacher (yet)

A source of guaranteed accuracy

Creative — in the human sense

A replacement for human judgment

Immune from bias

A reliable source of emotional guidance

AI doesn’t “understand” anything.

It predicts — what words are likely to come next, what questions you might ask as a follow up, and what your preferences are based on previous interactions.

That doesn’t diminish its power — but it should clarify the boundaries.

And students must learn those boundaries the same way they learn grammar, research methods, or digital citizenship.

What Educators Asked Most Often

Across three sessions, the same questions kept surfacing — a good signal of where educators really are right now.

1. “Is AI helping students think, or bypass thinking?”

Fair question. The answer is: both.

AI accelerates idea generation, but it also accelerates shortcuts. The key is intentionality and structure. In the same way that calculators didn’t eliminate the need to know basic math, we still need to teach students the critical and creative thinking skills to understand how to use AI as an effective tool.

2. “How do I prevent cheating?”

You can’t. Not entirely. Kids will take the easiest path, if we let them. And no, those AI’s that promise to identify generated text aren’t a silver bullet. As the models continue to get better and better, cheating will become harder to spot (and no — the use of em-dashes is not a sure-fire sign of AI).

So what can you do? Design assignments that inherently require process, reflection, and comparative reasoning — things AI can’t fully replicate without the student being engaged. Ask students to use the chat (or voice) function of AI to challenge their thinking or hypothesis, identify alternative view points, and push-back on generated responses to identify potential hallucinations or counter-arguments. Make the AI part of the process, not the forbidden fruit.

3. “Will AI replace teachers?”

No. And that’s not me being optimistic.

Yes, AI can teach. It can deliver content, provide answers, generate and score tests, and even engage the students to differentiate and build understanding at their individual level.

It can replicate the tasks of being a teacher. But one thing it can’t replicate — at least not yet (and probably not in our lifetimes) is connection, relationship, motivation, or contextual judgment. I still remember Mr. Taylor, my 7th grade biology teacher. He didn’t just teach science — he instilled a love of the scientific method, critical thinking, and analytical mindset that I use to this day as a digital strategy consultant. He engaged students with his quirky nature, lame science jokes, and approach that showed his own love of the material. That’s something that’s still impossible to replicate with AI.

4. “How can AI save me time?”

This was the most common question, and a good follow up to the question of “will AI replace teachers!” AI can summarily replace many of the rote tasks of being a teacher — lesson planning, rubrics, email drafting, differentiation, text-leveling, resource creation, etc. It can also help generate starting points for better brainstorming and ideation, targeted testing, and breaking down concepts for better teaching. More importantly, AI can free you up to be more present in a world where students desperately need your presence. I know it’s cliché, but it’s true: teachers who choose to partner with AI, will outperform those who try to ignore it.

The Framework: Caution, Curiosity, Courage

In each session, I offered a simple posture that educators can use to ground their approach, based on a simple concept: we can’t ignore AI, we need to address it head on… but that doesn’t mean abandoning our concerns. We have to approach AI with Caution, Curiosity, and Courage.

Caution

Caution doesn’t mean leading with fear. AI is powerful, but it’s also imperfect, biased, and sometimes overconfident. Instead, we need to focus on building clarity, well-defined boundaries, and maintaining a strong internal compass.

Curiosity

AI can feel overwhelming — there are a lot of paths that teachers and students can take, and not all lead to making teaching and learning better for everyone. Teachers and students should feel free to explore, but not pressured to adopt everything (or anything). Explore what’s useful for you — iterate, share with your colleagues and classmates, and find ways that to incorporate AI that feel natural and helpful.

Courage

AI adoption is a spectrum, not a light switch. It can feel completely foreign and uncomfortable to some; second nature to others. But inconsistency in adoption can also be detrimental to learning. Institutions should set expectations and policies that make sense for their users (student age, curriculum, etc.), while encouraging greater uniformity in adoption.

THE BOTTOM LINE: When it comes to AI, Avoidance as a policy, is a losing strategy. It doesn’t protect students — It leaves them unprepared for a world that will expect fluency.

What Students Actually Need in a World Shaped by AI

AI doesn’t require a brand-new set of skills. But it does raise the stakes on the skills we’ve always cared about.

The hours I’ve spent working with educators has made that shift clear. The focus shouldn’t be on what students need — but rather how those same skills can become levers for success in an AI-powered world.

Because students will delegate the “searching” to AI. Which means the persistence, resilience, problem-solving, and conceptual understanding has to shift somewhere else.

So how do we activate those neural pathways that lead to deeper understanding — where long-term learning and growth happen — without AI over-assisting?

We need to move from knowing what to ask, to knowing how to ask. In other words, the skill of “searching” needs to become a skill of “interrogating.”

Instead of “How do I get the answer?”

It’s “How do I know the answer makes sense?”

Instead of “Can I write something?”

It’s “Can I distinguish between a convenient summary and real understanding?”

We’re reframing skills, not changing the standards:

asking sharper, more specific questions

analyzing and evaluating answers

comparing perspectives instead of accepting the first result

verifying sources, context, and plausibility

spotting contradictions and ambiguity

thinking probabilistically (because AI is probabilistic)

building arguments that reflect their own reasoning

collaborating in ways that AI can’t replicate

communicating clearly across mediums

creating original work, not just remixing prompts

sensing when something feels “off,” even when it sounds authoritative

The Mindset Shift Students Need — and the Mindset Shift Educators Need to Support Them

Some educators have told me that this shift feels like moving the goalposts closer in — but not in a good way. It feels like AI removes the productive struggle that builds persistence, emotional regulation, and that “slow burn” cognitive growth we know supports long-term learning.

That concern is valid.

AI does make it easier to get to an answer.

But getting to an answer has never been the endgame.

Learning comes from everything that happens before, and after it.

So instead of viewing AI as undermining the struggle, we need to redefine where the struggle happens. In other words:

If AI lightens the work of searching,

we have to double down on the work of understanding.

This is where the educator’s role becomes more—not less—important. Teachers become the guides who help students:

stay in the question longer

compare interpretations

articulate reasoning

sit with ambiguity

recognize when an answer is too easy

push past convenience into deeper cognitive territory

And that’s the actual mindset shift:

Not “AI makes learning easier,”

but “AI moves where learning needs to happen.”

That’s a professional judgment call — something no model can replace.

Preparing Students for a World Where AI Isn’t the Future — It’s the Environment

As AI lowers the cost of generating output, it raises the cost — and value — of human discernment.

The future of education doesn’t need to be AI-driven. But it does need to be AI-enabled — even if it happens gradually. This is why as both a parent and AI advocate, I believe in a scaled approach. This means:

Early grades stay focused on foundational thinking skills.

Middle and high school become the testing ground where students apply those skills with AI, not against it.

Colleges expect students to bring AI fluency into complex, discipline-specific work.

Employers assume AI will be part of every role, every workflow, every decision.

That’s the continuum our kids are walking into. And the niche — the opportunity — for educators is enormous:

Help students develop the clarity, judgment, curiosity, and creativity

that AI cannot automate.

The future of education can’t be about competing with AI or determining the perfect case for integrating it’s use. It’s about preparing students for a world where AI is simply part of the operating environment.

And educators — with their experience, their humanity, and their deep understanding of how learning actually happens — are uniquely positioned to lead that shift.